The Public Policy Organization hosted a forum on Sept. 26 to share the testimonies of participants or “dreamers” in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

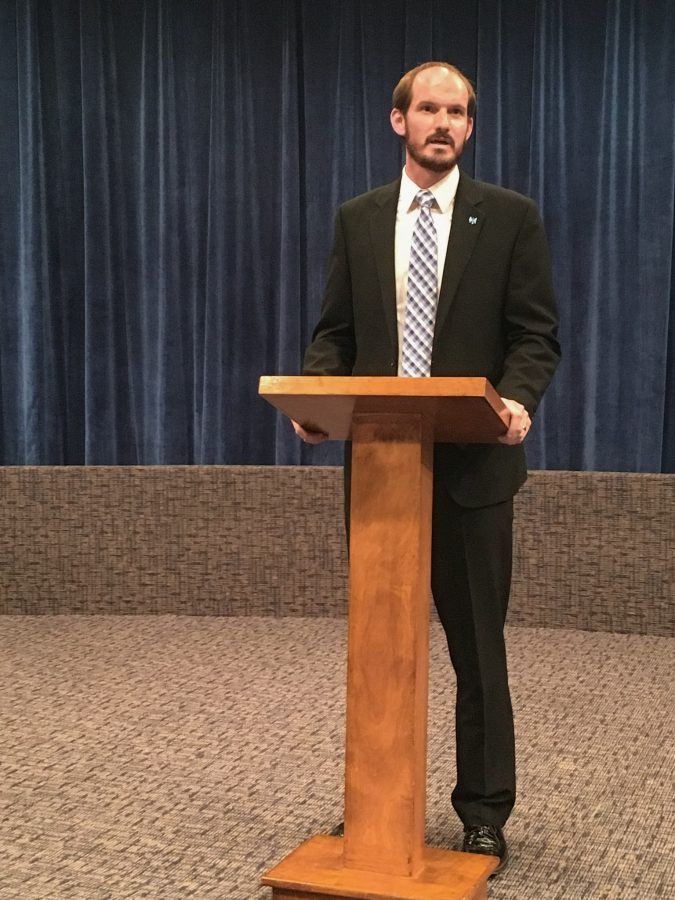

Two BJU dreamers, one of whom wished to remain anonymous and Luis Morga, a freshman business administration major, were unable to attend but had their stories read by Dr. Jeremy Patterson, chair of the Division of Modern Language and Literature.

Testimonies were also given by students from Furman University, the University of South Carolina Upstate and Lander University. A BJU graduate, representating the non-profit organization Hispanic Alliance also spoke.

This organization aims to connect the Hispanic and Latino community with the broader community.

The DACA program, created by President Obama in 2012, allows children brought to or remaining in the U.S. illegally to receive a renewable two-year period of safety from deportation.

The policy enables undocumented minors to be eligible for work permits and driver’s licenses if they qualify and pay application fees to enter the program.

Entrance into the DACA program required that the dreamer have entered the U.S. before age 16, have lived in the U.S. continually since June 15, 2007, pass a background check and be a student or have obtained a diploma or GED.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the end of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program on Tuesday, Sept. 5, with a six-month delay in the termination to allow Congress to address the issue.

The decision to revoke the DACA program was met by a wave of media coverage of the potential effects to undocumented minors.

According to participants in the PPO forum, the decision has caused fear and anxiety as they anticipate the uncertain future.

Ilse Isidro, a senior nursing student at USC Upstate who works over 30 hours a week to pay her school bills, expressed fears of not being able to finish her education.

“Without DACA, I would not be able to finish my last two semesters of nursing school,” Isidro told the forum. “I will [also] lose my work permit that allows me to work at two local hospitals and my [driver’s] license.”

Elizabeth Garcia, a Furman University student from Uruguay, said she often overhears negative opinions about undocumented immigrants, including the belief that undocumented migrants desire to steal American jobs.

“When I hear them speak that way, I automatically think [to myself] ‘well, I guess you assume coming here was an easy decision or just because we wanted to,’ but it was not an easy decision,” Garcia said.

According to Garcia, her father lost his job and was unable to find a new one in the low- performing Uruguayan economy.

“Shortly before we came, we were selling our furniture, our tables, our chairs and our couches just to buy food,” Garcia said.

Garcia said her father believed coming to the United States was God’s will, but her mother had no desire to immigrate.

“The entire year before we came, she cried every day,” Garcia said. “She didn’t want to leave the life she knew of her friends, her family, her home [and] her city.”

Sara Montero-Buria, a 2007 BJU graduate and community engagement and strategy manager from Hispanic Alliance, said DACA students often work full-time jobs while they pursue their education.

“A lot of them work full-time hours to help their families and are still at the top of their class,” Buria said. “So to see some of them being held back just because of their immigration status is really sad.”

Linda Abrams, professor in the Division of Social Science, said the DACA issue should be seen as a separate issue from the broader issue of illegal immigration.

“The DACA students are different because they have been granted status, albeit secondary status, here in the U.S.,” Abrams said, “which means that now the government has all their information.”

Abrams said DACA students could now be some of the first deported even though they are working or in school and were willing to come forward and register when other undocumented immigrants would not.

“These are the best of the best,” Abrams said. “And they’re likely going to be the first ones to be deported, which of course is problematic.”

“The other problem is that these people are culturally American. We aren’t talking about people who don’t speak the language,” Abrams said. “One of the main problems with illegal immigration is that illegal immigrants don’t assimilate, but that’s not who these people are.”

Patterson compared his experience growing up in Japan to the dreamers’ experience in the U.S.

“They’re more American than I am, folks,” Patterson told the attendees at the PPO forum. “I didn’t grow up here, and the fact that they could be ripped out of their homes and their country is terrifying.”

According to Patterson, a practical takeaway from the forum was for citizens to contact those who represent them in Congress.

Patterson said the theme of the event was to think more broadly on the issue of immigration.

“On every political issue, we all and myself included tend to get tunnel vision,” Patterson said. “We hear one thing from one friend, one parent or one teacher and that’s how [we think] it is.”

Mark Haxton, a junior communication major, said attending the forum did not change his opinion on the need for the repeal of DACA, but it did give him perspective.

“My perspective on who dreamers are did [change] and definitely [my perspective on] the thought process behind their immigration to the United States,” Haxton said. “I always thought of them as illegal immigrants…but now I understand that they have reasons to come to the United States, whether they be right or wrong reasons.”

The Trump administration has given Congress six months to create a permanent solution to the DACA issue before the program expires on March 5, 2018.

If no decision is made, nearly 800,000 dreamers, including six BJU students, could lose their legal status.