Twelve-year-old Rafael Costa was younger than the rest of the contestants. At least 15 years younger, on average, and the more experienced jet Ski racers were certainly not expecting a ysoung boy to provide such stiff competition in his first race ever. But while young Rafael Costa was probably as unfamiliar with Shakespeare as he was with jet ski racing, greatness was being thrust upon him.

Costa’s father purchased his family’s first Jet Ski when Rafael was 12, and the Costas soon began taking trips to the nearby lake to ride. It was on one of these trips that Rafael began to race. “There was a special competition that day, in the same lake, and they were short by one to make the race official. They started asking people who had jet skis,” Costa said. “My dad was like, ‘Hey Rafael, you do the novice race.’”

So Costa competed against several adults in the novice competition, and he won second. His career in jet skiing had begun.

After seeing his son’s natural talent, Costa’s father decided to push his son, still on his first day of racing, into a bigger challenge. Mr. Costa had signed up for the Superstock race, the highest level of competition for older, more experienced riders, but he thought his son would do just fine in his place.

“I remember well that I had to borrow a helmet, because I didn’t have one, and [I had to] borrow a better lifesaver because mine was too cheap,” Costa said. “I can’t imagine doing that with my son, letting him race when he’s just 12 years old.”

The race started, and three of the veterans were penalized for false starts. Thanks to his natural racing instincts and his advantage over the three penalized competitors, Costa placed third in the Superstock. What Costa and his father didn’t know beforehand was that the top three participants would qualify for the state-level race.

Costa said, “They came to me and said, ‘Hey, you’re just a novice and this is your first race, and this is the final race of the competition. We are going to let the other ones win the race. But you got third, and here’s your trophy, even though we can’t put your name on it.’”

Costa had been too successful — the officials weren’t ready to let him upset his adult rivals by advancing him to the state level yet. But people knew who he was now, and his future was bright. Following that race, Costa won several races in his city and state, but competing in other states was still a difficulty for the budding racer. “They didn’t allow me because I was underage,” Costa said. “I had to get a judicial order to be allowed to race.”

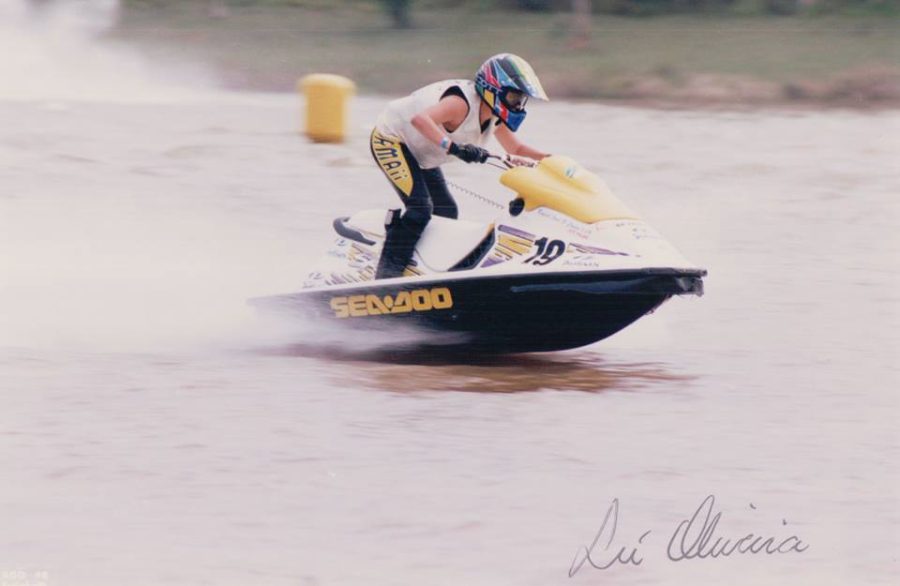

This didn’t hinder Costa, though, and he won his official state competition by the age of 15. His age didn’t stop giving him trouble, though. “They didn’t let me race at the national level until I had won two other races from two other states,” Costa said. It didn’t take him long to secure two other state victories, though, and by age 17, Rafael was the Brazilian national Jet Ski champion. The next closest competitor in age was 25.

The high school-age racing phenom was now eligible for the world championship, and Yamaha representatives soon came knocking at his door (he rode a Sea-Doo). They offered him sponsorship for life if he could win third place in the world championship.

But Costa and his family had already sacrificed enough time and money for his racing, and he had to decline to participate. The world championship was a three-month event in the U.S., and it would have cost $30,000 to participate.

While Costa’s racing days were now over, he had other concerns, such as applying for colleges. He was applying to college in the U.S., but he needed to learn English first.

“We were asking which country speaks English and is the cheapest, then we found New Zealand,” Costa said. He then spent six months in New Zealand before moving to the U.S. to study at Yale, the school at which he had been applying for a scholarship. Costa continued to learn English and study at Yale, but his heart began to pull him elsewhere. “God started talking to me, about what kind of future I was going to have,” he said.

His pastor had attended BJU and urged him to consider the University. Costa longed for a Christian environment and a smaller school bill (his scholarship at Yale still left 50 percent of his tuition unaccounted for), and he soon came to study at BJU, where he is currently studying mechanical engineering, a field that suits him well.

Costa and his father spent many long hours tinkering with his Jet Ski and making it the fastest and most well-tuned machine on the Brazilian racing circuit. Rafael Costa is most likely done with competitive racing, but his knowledge of jet skis will certainly influence his future. He speaks of building and fixing jet skis and passing down his love of racing to his children in the future.