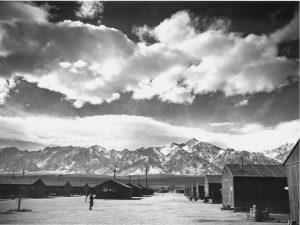

The Upcountry History Museum — Furman University is exhibiting a series of 50 photographs by Ansel Adams documenting the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. The display will be shown through Oct. 31.

Ansel Adams, who was a landscape photographer from California, photographed the Manzanar Relocation Center, an internment camp for Japanese Americans, in 1933 and 1934.

According to Kristen Pace, the education and program manager at the Upcountry History Museum, Adams received permission to take the pictures from the center’s director, whom the photographer knew from the Sierra Club, an environmental group in which they both had membership.

Adams documented life at the internment camp through his art of photography, turning his lens from landscapes to the lifestyle the Japanese Americans were forced to adjust to.

Pace pointed out the domesticity of Adams’ subjects: portraits of people adjusting to new life in the barracks they now called home, playing baseball or volleyball and farming or making clothing.

Photo: Submitted by Upcountry History Museum — Furman University

“It’s highlighting daily life,” Pace said. “There is definitely more focus on the portraits of the people. … You see a lot of smiles, almost like happy faces.”

His portraits show the resilience of these Americans. While they were denied their freedom and basic rights due to where their ancestors immigrated from, they did not let social injustice stop them from having hope. “They were still dedicated to the cause of American democracy and freedom,” Pace said.

“They were American citizens; they had their own homes and businesses,” she said. “Many of them were thriving. Some were more than willing, wanting to be drafted or even enlist to serve, to fight for the American cause, … but because they had that Japanese ancestry, that tie with families in Japan, they were seen as the enemy.”

During World War II, the U.S. government looked on Japanese Americans with suspicion after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, fearing they would spy for the Axis powers because of their ancestry.

Dr. Brenda Schoolfield, the chair of the Division of History, Government and Social Science, said the U.S. used curfews and evacuations to round up the minority group.

“President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942 to evacuate any person deemed dangerous from the West Coast to ‘relocation centers’ inland, away from the coast,” she said.

This culminated in over 112,000 Japanese Americans being sent to 10 relocation centers to keep assumed spies from colluding with the Japanese. Of these people, 11,070 were sent to the Manzanar Relocation Center.

But this led to innocent men, women and children being extracted from their lives all over America and placed into a new setting 220 miles northeast of Los Angeles.

“None of them were accused of crimes against the U.S. government,” Schoolfield said. “[But] if families could not secure or dispose of their property before the military came for them, the families lost their property.”

For the first time, people outside the relocation center saw the life the Japanese Americans were forging for themselves at a 1945 exhibition of the photos, but the exhibit was closed after stirring controversy about the ongoing war.

Anyone interested in the exhibit can visit the Upcountry History Museum Monday through Saturday. The museum offers discounted admission rates for students who present a valid college ID.

More information is available on the museum’s website at upcountryhistory.org.