The city of Greenville was home to one of the greatest stars of baseball, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, former Chicago White Sox player with the third highest batting average in baseball history and the highest batting average of a rookie in a single season.

John Nolan, a guide with Greenville History Tours and BJU faculty member, said Jackson is a hometown hero. “People embrace that he’s from here and are proud of it,” Nolan said.

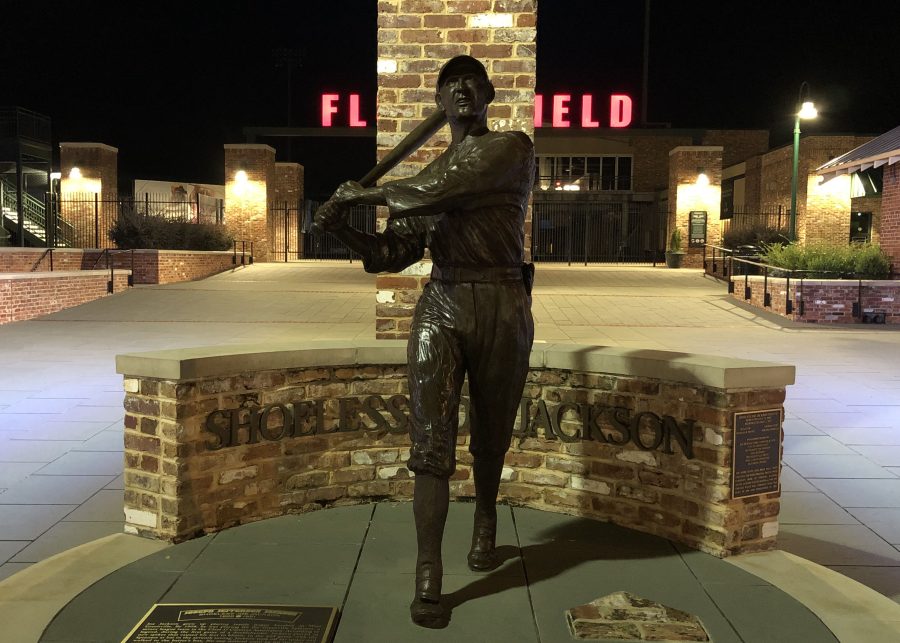

To honor this famous citizen, Doug Young, a BJU graduate and former staff member, sculpted a statue of Jackson that was first placed at the corner of Main Street and Augusta in downtown Greenville. Young worked on the statue in Greenville City Hall, where the public was invited to watch the sculpting process.

Fluor Field, home of the Greenville Drive baseball team, opened in 2006, and the Shoeless Joe statue was moved to the ballpark in 2017. All that remains at the statue’s old location is a circular base made of bricks taken from the Chicago White Sox’s Comisky Park after its demolition.

Joe Jackson’s life began in rural Pickens County, South Carolina, about 22 miles from Greenville, in July 1887. Shortly after Jackson’s birth, his family moved to Greenville so his father could work at Brandon Mill, a textile factory. Jackson began working at the textile mill himself when he was about 7 years old and never attended school.

Brandon Mill sponsored a baseball team, as many mills and factories of the time did. At 13, Jackson began playing “mill league” baseball. This is similar to the story told in Milltown Pride, a film produced by BJU’s Unusual Films in 2011.

Word of Jackson’s baseball skill, particularly his natural swing, began to spread. Jackson’s first job in professional baseball came with the Greenville Spinners in 1908. The Spinners fell into a Class D league, the lowest level of professional baseball.

Nevertheless, the $75 a month Jackson earned playing for them was nearly double what he made in semipro baseball and working in the mill combined.

Jackson’s nickname came out of his time playing for the Spinners. After wearing cleats that were too small, Jackson got blisters on his feet.

Because of this, Jackson took his shoes off partway through a game and played the rest of the time in just his socks. While Jackson never played barefoot again after that game, the nickname “Shoeless Joe” stuck.

Later the same year, Jackson’s contract was bought by the Philadelphia A’s. The big Northern city made Jackson—who still could not read or write—uncomfortable, and he returned to the South as quickly as possible.

During the next few years Jackson alternated between playing in Philadelphia and in the minor leagues in the South. When the A’s traded Jackson to the Cleveland Naps in 1910, Jackson became much more comfortable in Cleveland than he had been in Philadelphia.

In 1915, the Chicago White Sox bought Jackson’s contract. In 1919, Jackson became one of the eight White Sox players implicated in the betting scandal known as the “Black Sox Scandal.”

Nolan referred to this scandal as a cloud over Jackson’s career. Both friends of Jackson and baseball historians are not sure how Jackson was involved in the scandal or if he was fully complicit in the scandal. Nolan said that based on his good character on and off the field, many believe Jackson was treated wrongly.

Jackson was acquitted when he went to trial; nevertheless, the Black Sox Scandal ended Jackson’s career as a professional baseball player.

Jackson returned to the South after the end of his baseball career. At this time Jackson opened a dry cleaning business in Augusta, Georgia. He later moved back to Greenville and opened a short-lived barbecue restaurant. In his later years, Jackson ran a Greenville liquor store.

During his career Jackson was praised by other baseball greats of his time, including Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth.

Babe Ruth said, “I copied Jackson’s style because I thought he was the greatest hitter I had ever seen, the greatest natural hitter I ever saw. He’s the guy who made me a hitter.”